Powerful aliens meet in Cosmic Encounter. One of them, Chronos, has the power to go back in time and force the opponent to replay a battle if he loses. Another, Zombie, has immortal ships and Mutant always keeps 8 cards in hand, taking more of them from the deck (or his opponents) if necessary. The strangest of them all, the Schizoid, changes the winning conditions of the game itself, forcing other players to try and guess which one he has chosen.

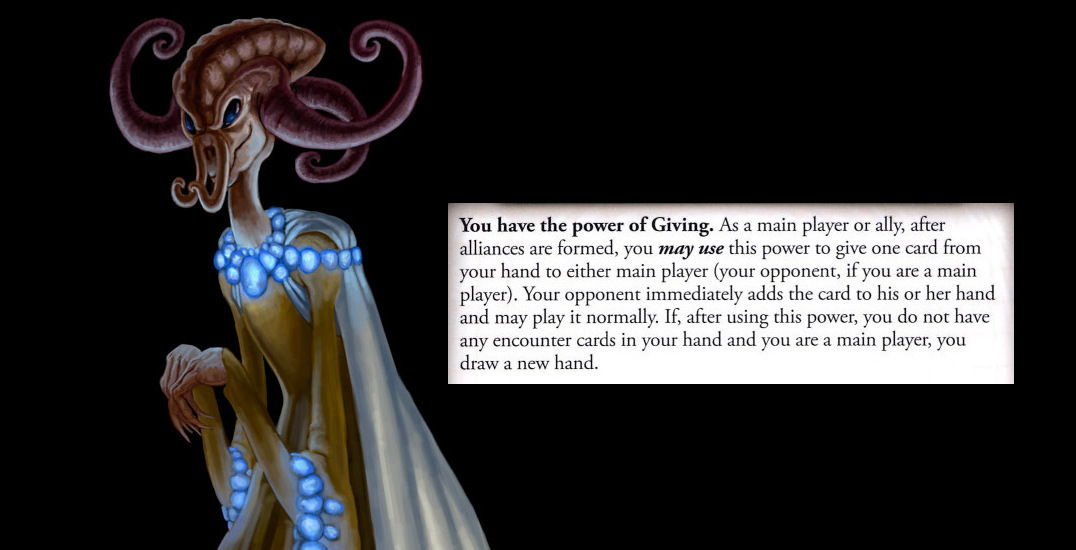

And then, there’s the Philanthropist. Compared to these powerhouses, it not only seems weak, but counterproductive. Why would you want to give cards to your opponent? Doesn’t that help them? Many players glaze over him, dismissing him as a joke or a narrow way to help an ally.

But not only it’s a tremendous power, it’s an insidious one and also a great piece of game design.

To understand how Philanthropist works one must first understand one thing about Cosmic Encounter: Players are forced to play most of their hand during the course of the game. With every encounter requiring at least one card, even the most skilled negotiators and defenders will see their hand dwindle in size over time, reducing their choices.

Normally this just requires planning ahead. You know which cards you have and what aliens you are bound to face so you can reserve cards for them. Play a few low attack cards first, when ships are plentiful, and you can get allies, and then bring out the big guns. If you do it right, you’ll play all your encounter cards painlessly and get a new 8-card hand afterwards.

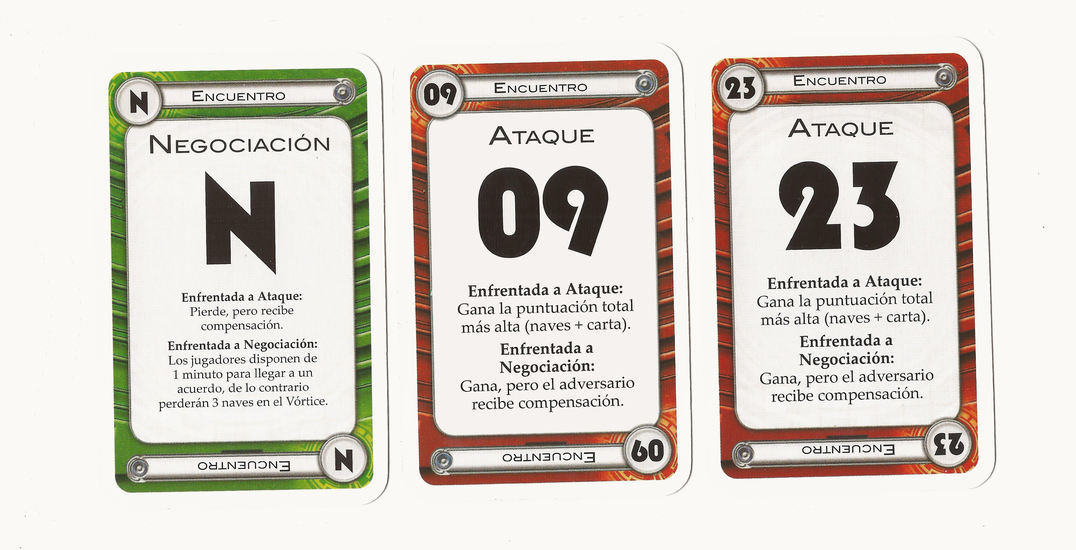

Or you would, were it not for the Philanthropist. Every time it’s your opponent it’s going to give you a card. And it won’t be a good card. It will be something low, like a 04, or a Negotiate you don’t need or want. And, like all other cards, you won’t be able to get rid of it unless you play it.

It’s a poisoned gift. As long as the card remains there you won’t get a new hand but if you play it, you’ll probably lose the encounter. Whatever you do, you are doing the Philanthropist bidding. It was its card and its choice to give it to you, but it’s you who has to deal with the consequences.

Meanwhile, the Philanthropist reaps the benefits of pruning his hand. By giving away all its low cards it can play only the very best of each hand and draw a new one afterwards. It keeps what he needs and gives away everything else.

Even better, these effects compound. It’s not just that you have better cards or that your opponents have worse ones, it’s both at the same time. Combined they form a strong advantage in a game in which small numerical differences often are the difference between winning and losing.

It’s an advantage strong enough to put the Philanthropist amongst the most powerful aliens in the game. It goes head to head against Antimatter, Trader or Clone. It gives Pacifist a run for his money and wins more games than Filch and Mind. He’s a threat, even if he doesn’t seem to be.

But what makes Philanthropist interesting as game design is not how powerful he is. Rather, it’s the idea of turning a nice gesture into something sinister that makes him so compelling. We are used to fighting, threatening and manipulating our way into victory, but giving? That’s not only something completely different to our understanding on how to win a game, it’s something in direct opposition to it.

Cosmic has often been described as being themeless. Compared to the likes of Eclipse or Twilight Imperium it’s a much more abstract game, to the point that many question its sci-fi status. But I think that Philanthropist proves that Cosmic Encounter is not science fiction because it has spaceships and aliens but because it asks, “If there were aliens with this power, this weird, incredible power, how would they take over the galaxy?”

And that’s a very fun, very sci-fi question. Even better, it’s a question that becomes more interesting as you add others aliens into the mix.

In most games, Philanthropist is a pernicious alien. It does not win through violence nor does it actively harm its opponents, but it does manipulate them and disrupt their choices. Most of the time, when it uses its power, someone comes worse off.

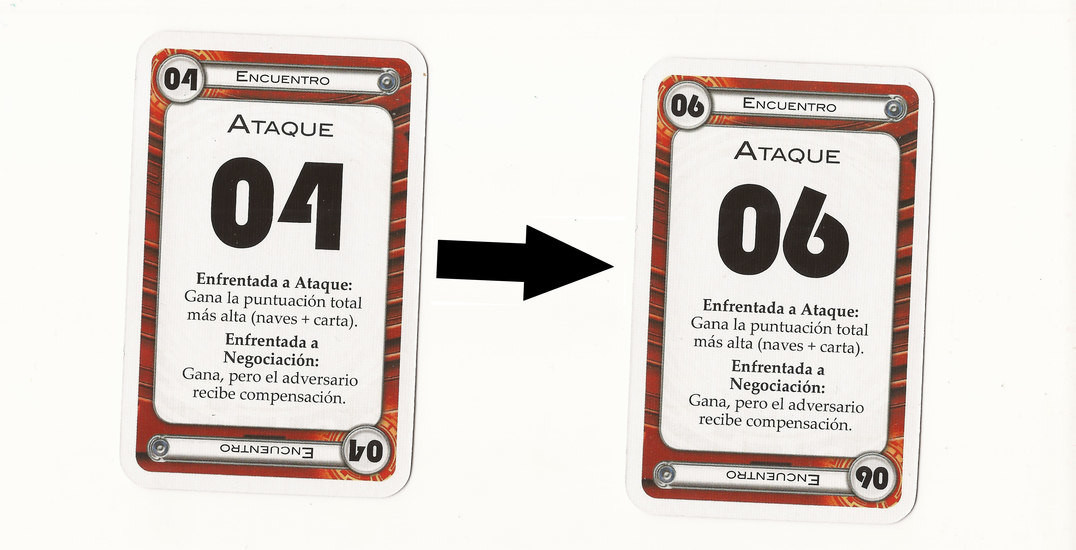

But if there’s an alien like Antimatter in the game, one starts to see a collaborative streak in the Philanthropist. You see, Antimatter radically changes the values of cards in the game. It wins encounters with the lowest, not highest, total and makes his own ships count negative. In order to beat it you don’t need 20s or 30s, you need a 06, a 04 or even lower, making those cards skyrocket in value.

So, the usual tactic of giving those cards to your opponents no longer seems a good idea. You are, after all, giving them the tools to beat Antimatter or even helping Antimatter itself. Even worse, you are getting rid of those tools yourself. With its ability of giving away bad cards reduced, it might seem like the Philanthropist’s power is no longer as effective.

But there’s also power in giving away good cards. Offered as a bribe, they can get the Philanthropist invited into encounters it otherwise wouldn’t have. You can let people have the card they need to beat Antimatter as long as they bring you along. And there’s power in that.

Power, but also nuance. It’s no longer about giving away “bad cards” to get “better ones”, it’s about manipulation through careful hand management. By putting the right cards in the right hands, the Philanthropist controls the game and, hence, the universe.

These aspects are so fun and so strong that it should not be a surprise to find out that Philanthropist is one of the most well-loved aliens in the game. It represents so many of the great things in Cosmic Encounter; the hand management, the tricky alliances, the subversion of expectations and pure, raw fun. It is not just one of my favourite aliens but one of my favourite pieces of game design and an amazing example of what games can be.