F-Zero never was technologically important. Published five years after Space Harrier and a year after Hard Drivin’ and its 3D graphics hit the arcade, its importance is rooted, not so much on novelty, as on bringing arcade advancements home.

It is, in fact, a fairly conservative game with more in common with old-fashioned classics such as Punch-Out that with a genre that progressed in leaps and bounds. And it is this traditionalism, not its technology, that has kept it relevant for almost thirty years.

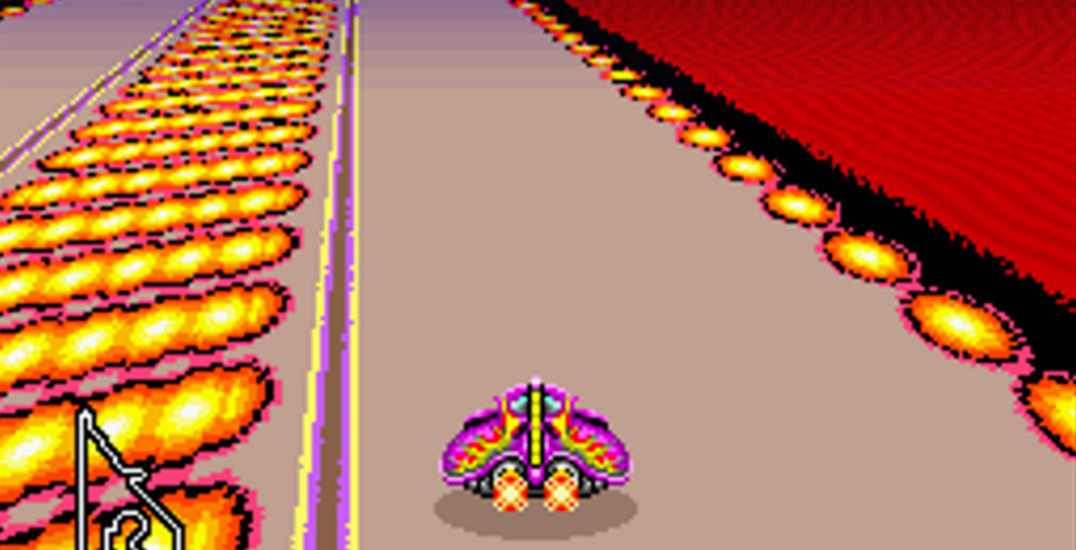

The racing cars of F-Zero don’t touch the ground. Rather, they keep themselves a palm above the ground through electromagnetic forces. They are futuristic hovercraft, pushed foward by 50s Sci-Fi rockets. They embody the game’s aesthetic and define it on a mechanical level.

For example, they slide when taking curves at full power. But they can also make very narrow turns by tilting to the side until the car’s structure hits the ground. These two effects, combined, allow for a large amount of paths through a circuit and many different ways to take each curve.

It is possible, for example, to take them with a soft press of the brake or by tilting the car to drift. Sometimes the fastest way to take a curve is to hit the floor hard while, in others, it’s a waste of time and energy. Sometimes even the walls of the circuit can be used to take a tricky curve, bouncing against them as if the car were a pinball.

All these movements give richness and texture to a game that would otherwise be a touch too simple. F-Zero is not a game with a very strong level design. In fact, the difference between some circuits often boils down to one or two curves. Opponents are mostly generic, with only a handful of unique racers with no visible personality. The game is so simple that it doesn’t even have an intro video like most other SNES games have.

To palliate this issue the game gradually introduces a series of obstacles during each campaign. The first are “boosters” which, like their name implies, give racers a boost if they touch them. Following them are jumps, often mortal and sometimes necessary to quickly take a corner. And on more advanced circuits the game introduces mines, magnetic railings and slippery zones where the car’s grip is loosened.

These are the kind of mechanics that often go wrong. Nobody plays a racing game because it includes a large assortment of obstacles but because its mechanics or level design are great on their own. But F-Zero‘s obstacles are not meant to be punishing. Rather, they support and compliment those two key aspects of the game, changing the way one drives through the circuit.

Even then, F-Zero is but a minor constellation. It’s a game too small, too humble to be mentioned alongside other Nintendo classics and a touch too traditional to compete with the masterpieces of its genre.

But even if it doesn’t reach those levels, F-Zero is worth playing. It has that traditional Nintendonian touch and its strong art direction compensates its now-dated graphics. It puts its weight where it matters. It’s a game that I’ve never regretted playing.

| F-ZERO (1990) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| DESIGN | Kazunobu “Isshin” Shimizu | PRODUCTION | Shigeru Miyamoto |

| DEVELOPMENT | Nintendo EAD | MUSIC | Naoto Ishida, Yukio Kaneoka, Shigeki Yamashiro |