Most logical deduction games get less interesting after a few plays. Faced with the same puzzle every time, strategy quickly becomes repetitive. The Search for Planet X, however, is one of the few that has actually gotten better the more I play it. With two difficulty modes and plenty of opportunities to lean on your opponent’s research, there’s room to play better. It all starts with a little survey, some wild theories and ends with a scientific breakthrough.

HOW TO SEARCH

The Search for Planet X is built around two principles. The first is that less precise information is more efficient. The second is that you must publish your results every couple turns, even if you aren’t ready for it! Any successful investigation will balance both. Of course, this is easier said than done as they represent opposite ends of the deduction spectrum.

I usually start with the broadest search possible. The wider our search, the more sectors we gain information on. This gives us a better chance to see patterns, like asteroids clustering together or half of the map being empty of comets. Since not finding an element implies it must be something else, this is the quickest way of getting a general idea of where things are located.

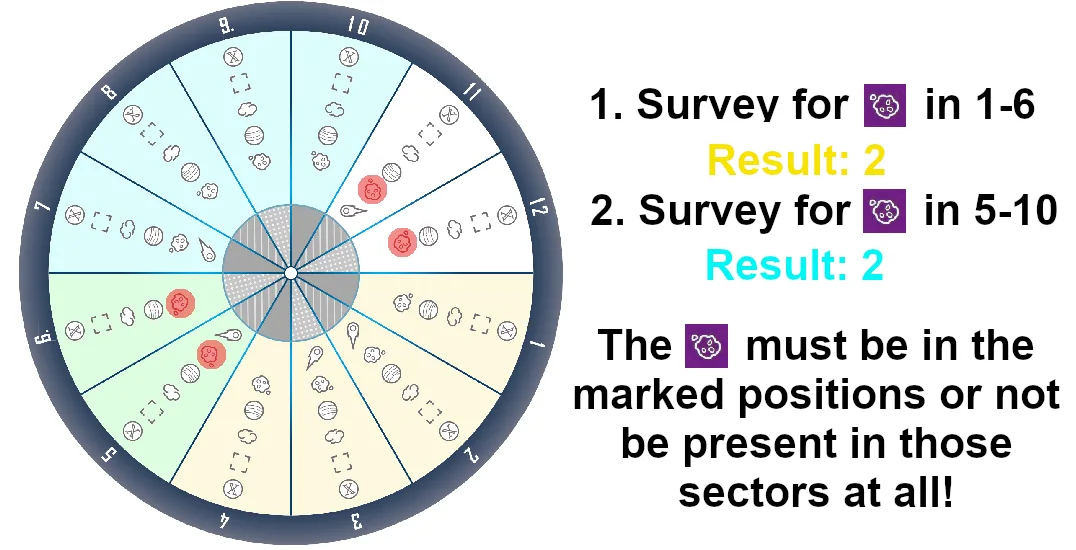

Give your actions some overlap. For instance, we can research a pair of elements and then survey the sky for one of them. We can then make it cover a couple of sectors already covered by another. This allows us to compare one to another, which can be illuminating. In fact, this is my favourite way of finding asteroids. They appear either in clumps of four or in pairs, which makes them easy to detect through this method.

Here’s a practical example. Imagine we search for asteroids twice, leaving an overlap of 2 sectors. Both times we are told there are two. What does that tell us? For starters, it means the asteroids aren’t crumpled together in a group of four. They appeared in pairs. Hence, there’s either just one group in the overlap or two different groups outside of it.

Even better, if there’s a group in the overlap, the other must be in the spaces we haven’t scanned yet. If there are in two in the surveyed area, then we know they are right at the edges. Both cannot be true so if any minor details contradicts either possibility, we’ll know exactly where every single asteroid lies. By giving our actions some overlap, we obtain precise results while taking advantage of the most efficient methods in the game.

You can apply this principle to exclude sectors from your search. Remember, if an element is not in one area it must be in another. But don’t worry if all this goes over your head at first. The Search for Planet X would be boring if we all played perfectly, wouldn’t it? Like always, my suggestion is just to try it. There’s nothing wrong with losing the first time if you do a bit better in the second.

PUBLISH, PUBLISH, PUBLISH

We’ve all been there. You barely had the time to sit down and take your first turn when the game barged in demanding an answer. One of the great things about The Search for Planet X is how quickly and often it tests our deductive skills. It’s not enough to reach out the solution in the end, you must provide results immediately or the busybodies in academia might cut your funding.

Don’t be afraid to publish theories. The penalty for getting them wrong is small. In fact, games are usually over before all of them can be checked, which means the true punishment is not getting points. Losing a bit of time won’t make you lose, but three or four points probably will. Hence, even a 50% chance of locating a comet or dwarf planet is a good bet.

With experience, this kind of gamble ceases to be necessary. There always are enough ways to obtain the information you need, even after just one turn. But you won’t get to that point if you don’t try! Not making the attempt is a more common and more serious problem than publishing the wrong theory. It’s natural not to try to make beginner mistakes, but don’t let that fear take over!

Note that it’s possible to take two turns before submitting your first theory. If you start the game with research or the ultra-wide survey available in the expert game, you won’t cross the research boundary. It’s not always the best way to obtain information, but if your initial slate doesn’t look great, it’s a possibility.

Once you get the hang of publishing theories, try to aim for higher value objects. Hitting comets is easy and finding both gives you 50% more points than asteroids. Scoring opportunities are scarce, so it’s a noticeable advantage. Often, players won’t be more than a couple points away from each other so you’ll win more often if you score Dwarf Planets and Gas Clouds and your opponent does not.

RIVAL SCIENTISTS

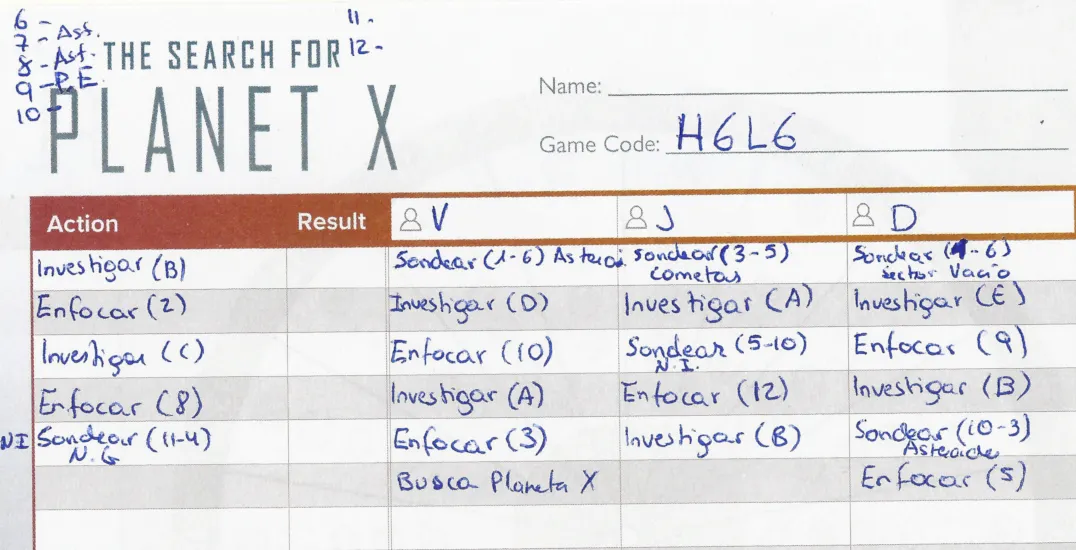

Much of the available information in The Search for Planet X comes from our rivals. We might not know what kind of results they have obtained but we do know what they were looking for. Those are clues in their own right. And there’s a lot of them! We only take one turn, but our opponents give us one tiny bit of information for every one of theirs. That’s a lot of stuff ripe for the taking.

So, first, please write down all your opponent’s actions on your sheet. It’s extremely important. Even if it doesn’t seem useful at first, it may be vital later. The game even provides a dedicated space for us to write it down. Every small scrap of evidence, no matter how small, can be the final step in the search for Planet X. It is one of the best aspects of the game and I can’t imagine playing without it.

But, how are we going to learn from our opponents when we don’t even know what they’ve found? The same way we figure everything else in this game, through deduction. More simply, if they have looked for a certain element, we can safely assume they’ve learnt something about it. Sure, it’s less reliable than seeing it for yourself, but it’s a great way to gain a little bit of additional information.

Imagine the rival to your left has taken a liking to comets. She started by attending a conference on the subject and followed up by searching the first few sectors. When the first research phase came up, she took a tile and put it in of the few spaces that could contain a comet. Can you figure out what theory she’s pushing forward? I bet you can!

Even if you haven’t looked for comets at all and know nothing on the subject, it’s safe to say she does. It’s the only information she has. Her theory must be on them, there’s no other element that makes sense. Hence, you can actually follow her lead and play your own theory on comets, in the same space as her. Sure, she might threaten to stop being your girlfriend if you plagiarize her work, but points are points, right?

You can extrapolate this to other situations. If your research leaves you undecided, check to see if your opponents know something you don’t. Try to guess what they are working on and if they have had results. Generally speaking, players will search until they find what they are looking for. If they are forced to survey twice, that’s a good indication that their first survey wasn’t successful.

Lastly, don’t forget to check their theories. Players won’t place them on empty sectors unless they make a mistake. That’s huge! Empty sectors not only reveal where gas clouds are likely to be, they are the only places where Planet X can show up. Still, I mark them down differently until they are revealed. I don’t trust my rivals that much! Just follow them enough to distinguish yourself with your own research. Good luck!