Tragedy Looper, Bakafire’s game of time travel, is getting new editions this year. This is great news as it’s an excellent game with a unique premise. However, the German publisher, Frosted Games, will not maintain the original setting. According to their podcast, they’ll move away from the anime artstyle and replace it with a Western one.

I believe this is a serious mistake. To westernize Tragedy Looper is to deny its whole identity.

TIME LOOP

In Japan there’s a burgeoning subgenre centered around time loops. Since the release of The Girl Who Leapt Through Time and its successful adaptation to the silver screen in 1983, the idea of characters being forced to repeat the same span of time over and over again has become a common trope. And nowhere is this trope more common than in anime and visual novels.

From otaku classics such as YU-NO to the eight almost identical episodes of Haruhi Suzumiya, the idea of escaping an endless loop with often fatal consequences has proven a fertile ground for artists. Even modern shows like Re:Zero and Rascal Does Not Dream of Bunny Girl-Senpai feature this theme, to the point it can be considered cliché.

Tragedy Looper is an attempt to bring these themes to the tabletop. From the stock shōnen protagonists of the cover, to its mechanics, it’s built to represent the ideas and setting of these kinds of stories. It’s a thematic experience with an inherent metatextual appeal.

We can see this resemblance through the two main influences of the game, Higurashi and Umineko. These two visual novels by indie developer 07th Expansion feature the core concept of Tragedy Looper: Characters stuck in a time loop, trying to stop horrible murders from happening and triggering the loop again.

Like in Tragedy Looper, the characters in these novels do not initially know about what causes these gruesome events nor the role other characters play in them. We see the mystery unfold and, as players or readers, try to figure it out with each loop. Violence and horror are omnipresent common, as are cackling masterminds.

There are also more than a handful references to both series in the game. The “Paranoia Virus” subplot that gives all characters the Serial Killer role is lifted straight from Higurashi, as is the Shrine Maiden. The art style is intentionally reminiscent of Umineko and there are mentions of butterflies, witches and other plot devices. Even terms such as “incident”, “culprit” and even “looper” are lifted straight from these two titles.

In other words, Tragedy Looper is a pastiche. It imitates a genre to celebrate it. Its whole identity hinges on its relationship to other works, in the attempt to bring them to the tabletop. It cannot be westernized for the same reason one cannot turn Once Upon a Time in the West into a fantasy series or remove Spielberg’s influence from Super 8.

WESTERN

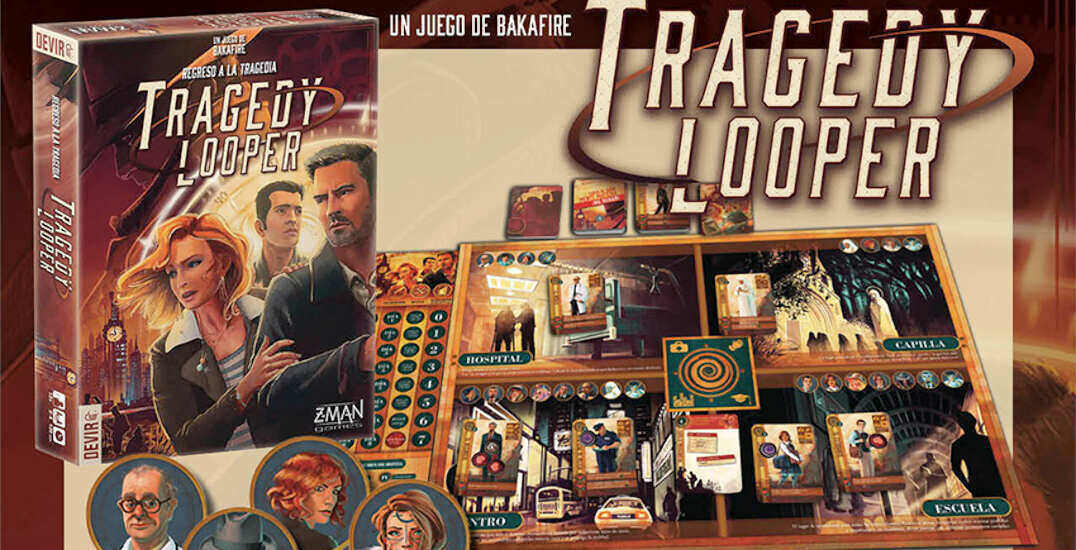

However, Tragedy Looper has already seen a Westernized release. Back in 2016, Spanish publisher Devir commissioned a different art style inspired by 1950s American police procedurals with a soft touch of “weird science” stories in the vein of The Twilight Zone. The protagonists are now adults and the Mastermind has gone from an exaggerated cackling villain to a subdued man in a fedora.

It’s a poor fit. One of the themes Tragedy Looper takes from its source material is coming of age. Ideas such as the loss of innocence, friendship and dealing with grief are reflected through its mechanics. However, these ideas are rarely the subject of the detective genre, leading to them being lost.

The introduction of older characters causes a shift in perspective. The spiky-haired protagonist and the Pierce Brosnan look-alike are not functionally equivalent. The latter is stronger, capable, independant. He doesn’t rely on authority figures. In fact, he is one himself. This undermines the inherent horror of the story.

Teenagers are in a position of weakness. Unlike adults, they rely on others. They have no power and their problems are often hand-waved away by those who could solve them. The horror of Tragedy Looper is not in the murder but in the idea that the people you look upon might reveal themselves to be murderers, conspiracy theorists or outright insane.

This ties into two central concepts of Japanese culture: Honne and Tatemae. Honne are our true feelings while Tatemae are the way we behave in public. As it applies to the game, characters might not be who they seem. We must break through oppressive social norms that tell us to look away to make things right. We must care where society doesn’t.

This is reflected through the “goodwill” mechanic. We can prevent horrible events by befriending others. Helping our peers and being honest with our feelings is an important aspect of Young Adult literature. It’s the power a teenager has. However, it’s not thematically appropriate for a hardboiled detective. Chances are Pierce Brosnan would rather shoot the villain in the back.

The subdued antagonist is also at odds with the game experience. There’s nothing better in this game than looking at the protagonists in the face and telling them they have lost, without telling them why. The massive information advantage and the arc of the game does not promote cold technical play but melodramatic villainous cackling.

Lastly, some minor details have been lost in translation. The brighter graphics, while easier to read, don’t communicate the same sense of paranoia and fear. The original characters were all a bit grim, as if they had something to hide. The newer set is cheerful, fitting for a Poirot novel, but not the gruesome realities of Tragedy Looper.

DIVERSITY

Above all, I don’t want to lose a valuable insight into another culture. For all the importance given to diversity in gaming, there’s still a pressure to conform to the same standard. Being able to enjoy foreign works through their own lens, is not given the importance it deserves.

I believe Tragedy Looper should remain Japanese because it has the right to be. There’s no need to change cultural artifacts just because they are foreign. There’s value in it, even if it also represents a barrier. It allows us to explore different views, cultures and ideas that are different from our own.

Westernization is oppressive and stale. It also begs the question. If anime tropes and art style are a problem, why choose Tragedy Looper at all? Few games are as difficult to divorce from their setting, unlike other anime-themed games like Bakafire’s own Code of Nine or Argent: The Consortium.

The truth is that a significant portion of the audience is interested in the game’s mechanics, but not in its influences. The average boardgamer has little knowledge of anime tropes and is not interested in them. Given this, it only makes sense for Frosted Games to sacrifice this aspect, no matter how central to the experience.

In that sense, a westernized Tragedy Looper is similar to the Netflix version of Death Note, Hollywood’s Ghost in the Shell, or the upcoming American remakes of Akira and Your Name. It’s the inevitable result of a medium afraid of looking beyonds its own borders and that undervalues its own cultural significance.