Of all area control games I’ve played, Liberté has the most challenging decisions of them all. Behind its French revolutionary façade lies an opaque game where players don’t directly control a faction. Matches can close with a narrow margin in victory points or end swiftly with a monarchist coup. It’s one of my favourite Martin Wallace designs despite a few shortcomings.

LAYERS

Liberté differs from the rest of its genre in that several majorities are layered on top of each other. The three factions – Royalists, Moderates and Radicals – are not directly controlled by any one player. Rather, players use cards to bring them to the board and then fight amongst themselves to see who has a majority on them. Only then can you reap the rewards of taking a faction to power.

Since there are more players than factions, Liberté raises an interesting dynamic. On one hand, you have to work with other players to make sure the faction you want comes on top. On the other, you also compete with those same players. This leads to a careful dance to see who benefits from the situation on the board.

Factions score points for their controllers by winning elections. There are points for the two players that contributed the most to the new government and also for the player that most helped the party in opposition. Everyone else gets nothing. Numbers are tight, with stacks being limited to just three blocks.

Being able to influence all factions at once opens many opportunities. It is possible, for example, to gain points for gaining access to the government and the opposition at the same time. A stack of monarchists may not be able to take the moderates out of power, but it can still gain control of the Vendée and its victory points.

Lastly, as the revolution progresses, France goes to war. Some cards have cannons in them and can be discarded to gain control of the revolutionary army. Take France to victory and you’ll be rewarded. Squabble to see who becomes its leader and France loses, making the anti-revolutionary forces stronger.

END OF TURN

All these elements have implications at the end of each round. For starters, there’s no fixed end point to them. Rather, a round is only over when one faction runs out of blocks. This means that each card drawn could represent one less opportunity to put blocks and vice versa. The tempo of the game is player controlled, a great dynamic rarely found in area control games.

Since stacks are limited to three, ties are common. We can “advance” one of our cards to break the tie but then we won’t be able to keep them for the next round. And what’s worse, if both players advance and tie again, their whole presence in the region is removed from the board.

But even if you win, you lose some presence. Votes are counted by taking a piece from your stack. Taking over the board with small ones may earn you more votes but also sees your results wash away by the next turn. This forces the choice between potential gains and risking an uphill battle with the next turn of the revolution.

These small details elevate the experience. They don’t make the game harder to play, but it introduces decisions that are not often found in the genre. Decisions are more proactive, more nuanced. The result might be opaque, but the strategy runs deep.

HISTORY

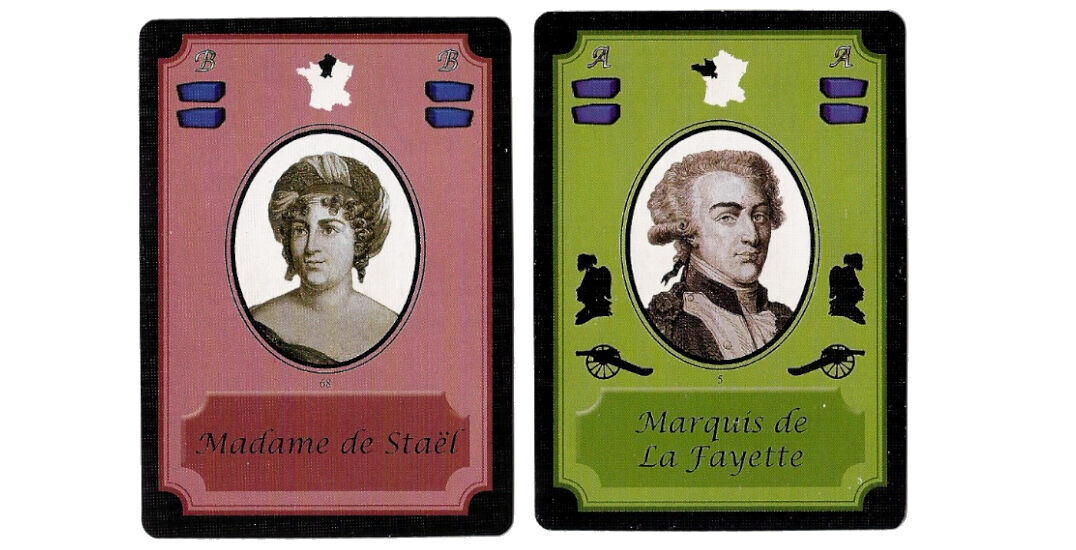

Like other Martin Wallace games, there’s a bit of historical detail. Special cards send characters out of France or to the guillotine. Some cards represent generals, capable of leading the country in war. Still, it’s mostly a game of pushing blocks and card play. If you are looking for a strong thematic experience, this is not the right title.

However, the historical background provides two victory conditions. At any point in the game, if either the radicals or the monarchists have grown too strong, the game ends immediately. All the points scored up to that point do not matter. With the whole power centralized in the hands of a few, only the player with the most blocks and cards of that faction wins.

This leads to an interesting dynamic whereby you can force presence on the board by threatening a win. For example, a royalist coup is triggered when certain regions are dominated by monarchists. Other players may not be interested in those regions, but they will have to compete for them if they don’t want to lose.

Conversely, if radicals get stronger players will attempt to join them in power. But if too many do and they become too strong, only one of them will win. While actual victories in this manner are rare, the possibility of it is strong enough that players must shape their whole play to prevent them from happening.

CARD DRAW

Sadly, Liberté suffers from a flawed draw mechanism. The cards have values of 1, 2 and 3, with the latter always being better. Some cards are not playable if you do not form part of the government or aren’t useful at all points in the game. There’s a real possibility of drawing a card you cannot use, wasting an action.

The Valley Games edition includes a variant with a small display of cards and allows you to draw – and play – the weakest cards in pairs. At first glance this is a good solution: Now the smallest cards are stronger, and you can avoid drafting special cards if you can’t use them. But it leads to problems down the line.

Since you play and draw more cards, the deck depletes more quickly. This wouldn’t normally be an issue except that the deck is composed of two halves, representing the changes undergone by the revolution. There are more monarchists in the first half and more radicals in the second. This means that, by going faster through the deck, you ruin its balance: Radicals become too common, too quickly.

Still, after playing with the original rules, I must say the variant is the best way to play. While problematic, it’s less of an annoyance than being stuck with a hand full of ones and unplayable special cards. Ultimately, this should have been solved by tweaking the deck’s composition.

VALLEY GAMES

This issue aside, I’m fond of Valley Games’ edition. It represents a massive improvement over the original, with appealing colors and easily recognizable areas. It may seem quaint in the age of Kickstarter and luxurious editions, but simplicity is what Liberté needs. Had the board been busier, it would have also been harder to gauge each player’s position.

After all, what I like about Liberté is not its historical setting but the depth of its mechanics. It’s not the kind of game that offers new thrills. Its understanding of area control is fairly traditional, it’s the skill of the implementation and all the small details that do it for me.

It might seem the game is overly complex. It has all the stacks, three factions, the control markers and a deck divided in two halves. But, at the end of the day, you either draw or play a card. It’s an elegant title. Its opaque strategy is part of the appeal, not an unintended side-effect of its mechanics.

| LIBERTÉ (1998) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| DESIGN | Martin Wallace | ART | Kurt Miller Mark Poole |

| PUBLISHER | Valley Games | LENGTH | 90 minutes |

| NUMBER OF PLAYERS | 4-5 (Best with 4-5) | SCORE | ★★★★ |