Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective is widely praised, but not without controversy. The scoring, which costs five points to the player for each clue taken, is often declared to be at odds with the narrative. In fact, many players and even critics recommend ignoring it completely.

I disagree. I believe the scoring is not only an integral part of the game, but an important driver of its aesthetics.

HOLMES

Consulting Detective strives to embody the spirit of Holmesian stories. It’s not a simulation, nor an attempt to model a real-life criminal investigation. Rather, it adheres to fictional conventions. No event is unexplained and no accident or random factor is necessary to solve the case.

Holmes is not a policeman nor a traditional detective. He values crime-solving as an intellectual exercise and is uninterested in the pursuit of justice or the legal ramifications of his work. Like the stereotypical British gentleman he’s polite but also cold and arrogant. He has a flair for the dramatic and enjoys showing off to others.

In other words, Holmes would not painstakingly follow every clue. Nor would he interview a suspect unless he needed to. To him this approach is slow and inelegant. It doesn’t provide the mental stimulation he seeks and wastes time in minutiae. Given the choice, he wouldn’t even move from the comfort of Baker Street.

The scoring promotes brilliant solutions based on acute observation, not rote detective work. Holmes works to eliminate possibilities by paying attention to small details. In his own words “We balance probabilities and choose the most likely”. Rounding up suspects and checking their alibis one by one is Lestrade’s work, not Holmes’s.

If this were a CSI game we would take DNA samples and track down criminals through government agencies. In one based on Poirot, we would talk and let culprits show their true colors. But this is a Holmesian game and hence the solution is unexpected, elegant and supported by a mere newspaper.

INDUCTION

Most importantly, the scoring promotes the use of inductive reasoning. This is a type of logic in which premises support the conclusions but to do not warrant it. It’s Holmes’s most valuable tool and what separates him from other fictional detectives. Let’s see an example:

- Mary was murdered in her home late at night

- John took a cab from a nearby direction that same night

- John is the culprit

That’s a bit of a leap, yet not an unreasonable one. There are other possible explanations, but it’s a good reason to suspect. If we find more circumstantial evidence this way, we can reach some surprising conclusions. Individually, each clue might not solve a case but together they all point towards the same solution.

By making us work with fewer clues, Consulting Detective promotes debate. The unreliable nature of induction creates a fertile ground for cooperation. Drawing potential turns of events and discussing how compatible are with the evidence we have is more engaging than raw mathematical deduction.

Most importantly, the game is designed to support this type of thinking. It provides enough evidence, signs, details to untangle the mystery. Anyone can put a puzzle together with all the pieces. But it takes a great detective to guess what the picture represents with half of them missing.

CONTENT

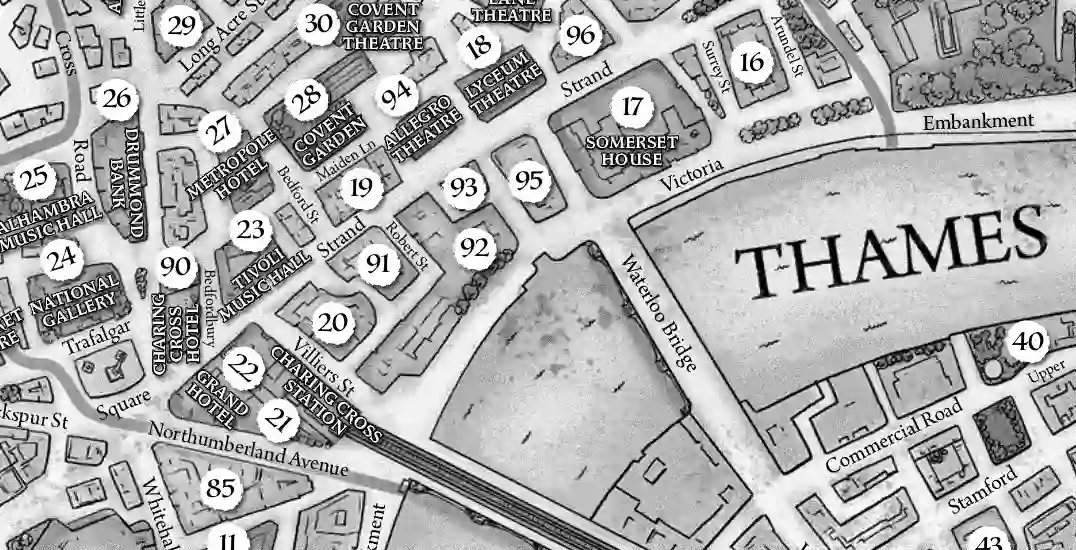

Regardless of the thematic implications, some feel the scoring discourages them from enjoying the game’s content. After all, interviewing suspects and immersing ourselves in the London of Doyle’s stories is a huge part of its appeal. By minimizing the number of clues, don’t we lose on what makes the game unique?

I don’t see it that way. The crime scene, the suspects and the game map are just the way to deliver the real experience which is solving a mystery. The substance of Consulting Detective is in reasoning, understanding motives and evaluating means, not reading.

It’s not different from any other game. The point of Terraforming Mars is not to play all its cards nor place every possible tile. Magic is not worse off by cutting cards from our deck instead of piling them up all together. In fact, we worsen the experience if we do. The same happens with Consulting Detective.

Truth to be told, there’s not much value to most clues. The majority of the information is located in a few key paragraphs. As we get further away from the crime scene and the main suspects, texts get smaller and less relevant. We might find confirmation for smaller details but that’s all.

In fact, some clues are redundant. For example, in one case there are ten different ways to obtain the same information about cigarettes. Reading them all doesn’t add much and it’s not particularly engaging. Consulting Detective is already a long, mentally straining game. Adding unnecessary information won’t make it more fun.

Like Holmes says, “A man’s brain originally is like a little empty attic, and you have to stock it with such furniture as you choose. A fool takes in all the lumber of every sort that he comes across.”